Increasing access to Europe’s wood resources

Key TECH4EFFECT report is released involving 20 partners from science and industry pointing to alternative managerial solutions, knowledge to better tackle climate change challenges.

A European collaboration of TECH4EFFECT (T4E) scientific and industry authors recently released a comprehensive report titled “Increasing access to wood resources” which has pinpointed the challenges for forestry, and provided recommendations for new knowledge-based principles for better management of the resource in mobilising wood for the bioeconomy.

Particularly, the report has singled-out the practices that have achieved an increase in forest growth-rates and improvements in the efficiency of forest operations, such as thinning and tending. The report’s conclusions have suggested alternatives to existing management methods that are currently carried out in European forestry to better fit the requirements of a modern bioeconomy with the aim of meeting the challenges of climate change.

The collaborative report, which was edited by Dr Johanna Routa, Adjunct Professor and Research Manager and Senior Scientist at the Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Dr Robert Prinz, Senior Scientist in Forest Technology and Logistics at Luke, and Benno Eberhard MSc from Vienna’s University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, BOKU, examined case studies from Finland, Italy, Poland, Austria, Norway, Denmark and France, and have recommended new knowledge-based principles for the forest industry.

Forestry has been described as both an art and a science. Its traditional roots speak to past and present, and the silvicultural practices and technologies used by forestry across Europe are as diverse as they are complex. Mobilising and managing timber resources across Europe, where fifty-one per cent of Europe’s forests are privately-owned, presents many challenges.

Challenges to wood mobilisation

Courtesy of the European Forest Institute

According to a McKinsey report (McKinsey: “Precision Forestry: A revolution in the woods”, 2018), there is insufficient corporate involvement in forestry, and the national state forest enterprises are mostly conservative in their management style. The editors of the T4E report have also identified in their Q&A answers the need for governmental regulation which would increase incentives for private entrepreneurs in an effort to boost wood mobilization, thus reducing the dominance of state enterprises.

Many factors drive the various management recommendations for Europe’s forests. There is no ‘one solution fits all’ prescription to management practices considering the differences in tree species, steepness of terrain, soil qualities, the historical evolvement of timber, labour shortages and most importantly the levels of mechanization that exist within Europe’s borders. In this context, an increase in mechanization is envisaged for the Central and Southern regions, whereas in the North carrying out tending and thinning in young stands needs to be applied to improve the growth rates of the remaining forest stands.

In addition, the focus on bringing forestry closer to Industry 4.0, a major aim of T4E, will depend on an increased uptake of digital tools and technologies to enable the next efficiency leap in forestry. Developing and offering new business models and online IT platforms where the mobilization of wood is facilitated by small owners using digital platforms for the wood tender process is recommended.

The authors of the report acknowledged and accounted for the traditional nature of the sector, and accordingly based the report on four main objectives:

- The increase of the access to wood resources; in general, not the wood production itself is the problem, but the access to wood resources.

- The efficiency-increase in silviculture; it basically is a traditional expression for the management of forest stands.

- The accessibility increases in the forest supply service business structure.

- The idea of upscaling the suggestions for improvement; it means to ensure a validity on a larger scale.

The detailed report can be read here: INCREASING ACCESS TO WOOD RESOURCES.

For those of you who want a quick summary of the report, T4E Communications asked the editors, Johanna Routa, Benno Eberhard and Robert Prinz about some of the most noteworthy points that could be taken up by the forestry industry and perhaps even by policy makers.

Who should read your report?

The target audience for the report is forest owners, forest companies, forest owner associations, in fact all people working in forest supply chains. In our report we introduce ways to increase the access to wood resources by identifying and promoting forest management practices that increase growth rates in forests and achieve measurable improvements in the efficiency of forest operations.

Explain the methodology of the questionnaire survey

The questionnaire survey was distributed to all partners involved in T4E Work Package 2 (Silviculture). Since the partners represent all parts of Europe, including North Europe, Central West, Central East and South Europe, practically all currently used European silvicultural management practices were covered in the survey. In this way we elaborated six essential systems currently in place, each of them being maintained by a corresponding cutting procedure.

In an age class forest which is composed of trees of the same age that either represent a single species (monoculture), or a combination of several compatible species, the harvesting methods of both clear cut as well as partial cut can be carried out.

In the short rotation forest, grown for fuel energy, or woodchip, a final cut is applied. The final treatment of coppice is clear cut, whereas the treatment of coppice with standard is a combination of partial cut where all trees on distinctive homogeneous patches of the stand get removed and selective cut.

The continuous cover forest, which is defined by selecting and harvesting individual trees, requires a selective cut. Finally, in the shelterwood system where a younger crop is established under the older canopy, the cutting of the shelterwood is required, which is in fact a multi-staged partial cut.

Describe the principal harvesting systems and their regional applications

Courtesy of the European Forest Institute

Harvesting systems can be classified according to the degree of mechanization. We can distinguish three basic types, and many types in between. The basic types are: (i) the motor-manual system, including chainsaw and a skidding device, for example, a forest tractor, (ii) the partly mechanized system, such as a combination of chainsaw and cable yarder, which is equipped with a processor head, and (iii) the fully mechanized system, such as a combination of a harvester and forwarder.

The degree of mechanization applied in a particular region depends mainly on four factors: (a) the steepness, (b) the soil bearing capacity; (c) the traceability; and (d) the size of the trees. In Northern European countries, for instance, where the portion of flat terrain is higher, and the size (diameter, height) of the trees is smaller than in Central European forests, fully mechanized systems are widely used. In Finland and Sweden forest harvesting is 100 per cent mechanized.

Why do you recommend an increase of mechanization in Central, Southern Europe?

Traction-assist winches allow ground-based harvesting machinery to be used on steep slopes making it suitable in mountainous terrain. Courtesy: NIBIO.

This argument refers to two characteristics of the abovementioned regions where, historically, mechanized options have been reduced due to technical limitations. This has been the case in the partially mountainous terrain of Central Europe and in Southern Europe where the silvicultural practice of coppice forestry is used.

However, due to an increase in technical devices and technologies now available, a boost in mechanized harvesting is anticipated. Our studies demonstrate that harvesting methods, which previously were considered questionable, are now no longer deemed unsound due to mechanized and technical advances. An example of this is the increased use of traction-assist winches in ground-based harvesting in steep terrain that reduces wheel slippage, which causes rutting and shearing. In addition, damages by mechanized harvesting systems on stumps in coppice, which are essential for the re-sprouting of the trees, are not significantly higher than after motor-manual felling, which is widely practiced in Southern Europe.

What are the benefits of mechanization?

More mechanization in harvesting means more safety for workers, enhanced efficiency after large area calamities, increased productivity and, therefore, cost efficiency.

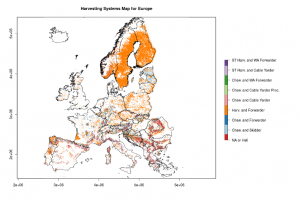

Tell us about the harvesting systems map for Europe

Courtesy BOKU

The harvesting systems map is a new digital tool that shows the Europe-wide suitability of areas that have been identified as being applicable for ground-based fully mechanized harvesting consisting of the harvester machine and the forwarder. The map takes into consideration the relevant and crucial aspects for controlling such operations, such as: (i) the steepness of the slope; (ii) the soil bearing capacity; and (iii) the forest road network. The map is an excellent tool to identify and verify the extent to which harvesting can be enhanced and implemented in forest operations across Europe.

Why does the report recommend an intensification of thinning?

Thinning signifies a pre-commercial treatment of a stand that includes the removal of young and thin trees, so that the margin (revenue minus harvesting costs) is small, or even negative. Thus, thinning should be considered as a stand investment which will bring higher financial returns.

By removing undesired trees, the manager concentrates on the resources of the remaining ones, which become larger and, accordingly, more valuable. Besides, the bad quality trees are removed, and in this way, the stand is able to rejuvenate by promoting genetically improved stock, which inherently will allow for more robust trees which are of better quality. Moreover, by generating thicker trees we increase the stability, or sturdiness, and sometimes we even increase the volume due to a reduction of the mortality, which means avoiding tree losses.

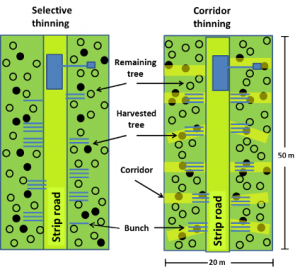

Tell us about boom corridor thinning vs selecting thinning, and tree marking

It is essential to carry out thinning at the right time, the right place, and to the right extent. Early thinning principally aims at increasing vitality, stability and productivity. Late thinning, in general, pursues quality criteria which is aimed at naturally debranched trunks with low stem curvature. In the context of climate change, along with an increased number of calamities such as wind throws and bark beetle attacks, fostering tree vitality as well as stability is highly advisable. T4E studies show that thinning at the right time is advantageous, and that on high-quality sites thinning even is capable of boosting the final volume of a stand.

The boom corridor thinning is an alternative concept to the selective thinning procedure. It concentrates on particular areas of a stand, by following a geometric scheme, and leaves the rest of the stand untreated. In total wood output, the same volume gets removed from the stand, so that the aim of thinning is fulfilled. This approach implies a reduction of the boom moves of the harvester machine and therefore is a cost-effective method in carrying out first thinnings.

Tree marking is a technique for the selection of the most promising trees in the context of thinning. The T4E study shows that it can be combined with a promotion of mechanization. Well-educated harvester drivers can select the right trees for removal. They perform equally as professionally as professional forest managers. The two-step procedure (tree marking by the forest manager and then actual removal by the harvester machine) gets reduced to one single work step where the harvester driver fulfills both tasks, the selection and the removal.

Courtesy Luke.

What are the implications for biodiversity?

The boom corridor thinning, by not accessing particular compartments of the stand, is favourable for biodiversity since the untreated areas retain an eventually present herbaceous layer and/or shrub layer. On the contrary, with the selective thinning methods, the machine encroaches on all parts of the stand. By fixating on a particular tree for removal, a path has to be cut for the boom to reach and capture that tree. This leaves an impact and therefore has an implication for biodiversity.

Why is tending at an early stage preferential?

Tending is considered an important pre-commercial measure, as is explained above in the context of thinning. Tending implies the first step of tree removal within the life cycle of a stand, and it is executed after the successful and ensured stand establishment. Besides the stem reduction, it includes tree species’ regulation which aims for a composition of desired tree species; the removal of badly shaped trees; and the re-spacing of the stand, which means that the trees also should be arranged in a regular order, as much as possible.

This measure depends on many factors, such as the involved tree species, the pre-defined production target, amongst other managerial aims. As a general rule, we can say that early tending, or intervention, captures the trees when they are in their full-growth spurt so that any additional resources due to a release in growth can be exploited fully.

Why is the Cutlink device in tending a better alternative to motor manual tending?

The further development and use of the Cutlink device would mean adopting more mechanization in the context of tending, with all the above-listed advantages of mechanization. By using this mechanized device, the problem of labour shortages associated with tending could be circumvented. However, this technology is not fully customized, but the intermediary results show strong potential. The T4E research paper studied the productivity of the Cutlink device compared with manual tending in spruce seedling stands in central Finland: https://bit.ly/3qzWixW.

Tell us about the studies conducted on the business tools across T4E

As a first step, a particular focus was on IT-tools, internet-based applications and other interfaces that enable both the requisition and marketing of silvicultural and harvesting services. The main IT solutions in three selected Nordic countries, namely Denmark, Finland and Norway were mapped.

As a second step, the main focus was on mapping the business processes of selected cases in Finland and Norway required in procuring services or forest-based products which enabled them to be systematically analysed.

Explain the benefit of the online IT platform vs. traditional enquiry

The produced process maps give an indication of the steps from a forest owner perspective when using an online IT platform. The case study used the number of interactions as an indicator of process efficiency of the alternatives. Benefits may include a reduced amount of data exchange processes for the forest owner and the reduction of processing time of data exchanges. However, the entire reaction and handling time in both cases still depends on the individuals involved, as well as the particular case.

Explain the benefit of having long-term forest agreements in place

Ultimately, forest management agreements may enable the forest owner associations to directly select forest owners’ stands for purchase and production planning. This effectively increases the planning horizon and the degree of freedom (flexibility) in production management.

Why should purchase lead times be reduced for initial contact with the forest owner?

While this will save time for forest owner associations purchasing, in general. The reduction in lead time would be most useful when deviations between reported production and production goals require rapid additions to the contract bank. It would facilitate the trade and supply of timber.

How could policy contribute to better silvicultural solutions to mobilize wood?

In some European countries we have dominant players within the forestry sector, such as the state forest enterprises. A change of the corresponding regulation for sure would release new incentives for private entrepreneurs and result in a boost of wood mobilization.

This project has received funding from the Bio Based Industries Joint Undertaking under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 720757.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr. Johanna Routa is adjunct professor, Ph.D., Research Manager and Senior Scientist at the Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke). Her research area includes biomass supply, quality management of energy wood, intensive forest management for biomass production, CO2 analyses and costs of different management practices.

She has participated in number of international and national research projects as researcher and project manager. Her current project portfolio includes the WP2 lead (Silviculture) of the TECH4EFFECT project, co-ordination of the Haiku project (energy biomass quality), co-ordination of forthcoming BRANCHES Project (Boosting Rural Bioeconomy Networks following multi-actor approaches), as well as other smaller projects.

She is the national team leader in the IEA Bioenergy Task 43 work and a Member of the Climate and Energy Group of the Regional Council of North Karelia.

Dr Robert Prinz is a Senior Scientist within the group of Forest Technology & Logistics at the Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke). His research speciality is in fully mechanised operations with a focus on improving the performance and energy efficiency of biomass supply.

He has been working as a researcher and project manager in several large EU-funded projects mainly dealing with international forest technology and know-how transfer, holistic supply chain design as well as dissemination and business adaptation.

Within the TECH4EFFECT project (www.tech4effect.eu; funded through the BBI JU/Horizon 2020) he is mainly involved in WP3 (Increasing productivity and cost-efficiency in timber harvesting and extraction), but also WP2 (To demonstrate the importance of rational business processes in procuring or marketing services for silviculture, harvesting and wood purchasing), in WP4 (Avoiding, reducing and documenting site impact) and in WP7 (Impact assessment).

Benno Eberhard is research associate at the Institute of Silviculture at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU), Vienna. He is engaged in the development of a forest growth simulation tool, with a special focus on modelling Douglas-fir stands. In this context he investigates the regeneration dynamics of Douglas-fir and its growth response to various management guidelines. In a further research-activity he explores the effect of thinning practices in boreal coniferous forest stands. He contributed to the results of WP 2 of the TECH4EFFECT project with a study on how to make thinning entries in European forests more efficient. Moreover, he was essential in designing and implementing the final report on WP 2.